Resisting the Loudness War

CDs are getting louder, and there's not much we can do about it.

What's the Problem?

I'm going to make a bold claim: I like music. I don't mean I'm one of those “whistle while you work” types; when I say that I like music, I mean it. I can sit down and just listen to an album, without doing anything else. I seek out new music, new bands and albums, because I want to hear new things. Hell, I even make my own music.

It's the last activity that's also lead to the most heartbreak. And it has nothing to do with harsh reviews, cruel audiences, or the ever-present threat of lingering in obscurity. No, what pains me most about making music is what I have to do to my recordings. I love creating music in a studio, from arranging the track to recording the instruments to making the final mix. But after I've done all these things, I have to do one more thing that makes my music sound lousier.

I have to squish my music.

Specifically, I have to compress it to remove some dynamic range. In laymen's terms, I have to make it sound louder. When you're mixing a song, it can only get so loud. There are places on the track where the music gets to be its loudest. With rock music, this often coincides with a snare drum hit. We call these places transients, and we call the loudest one the peak of the track. These peaks are slowly and steadily becoming the undoing of anybody who records music.

The reason why this is happening is because of the nature of digital recordings. When you represent sound on a digital medium (such as on a CD or MP3 file), you have to make a trade-off. In order to convert the sound waves made by an instrument or recording into a format computers can read, you have to pick a maximum sound level. There's no such limit for natural (we call them analog sounds). A sound in nature can keep getting louder and louder and louder, with no limit, until it kills you. When you digitize a sound, however, there's a limit, a cap, a point at which the sound can get no louder. When you digitize sound, you slice it up into tiny pieces, and every little bit of the sound (known as a sample) is expressed as a fraction of the maximum predetermined level. That's all a sound file really is (well, it's more complicated than that, but this is all you know to understand what I'm getting at). It's just a whole bunch of percentages of the maximum level in rapid-fire succession, in much the same way that animation is just a bunch of still pictures repeated quickly.

So I mix my tracks, and I have to make sure when I'm mixing that the sound never clips — meaning there aren't two or more samples right next to each other that are at 100%. If you've ever recorded a cassette tape, it's like making sure the needle never gets into the 'red area.' On an analog device like a tape recorder, a little bit of 'in the red' audio actually sounds pretty good; this is called overdriving the signal. However, if you get sound 'in the red' on a digital recording, then the track clips, which to our ears sound absolutely terrible. When you're mixing a song, a lot of work goes into making sure that things are as loud as possible without clipping. The only way to do this is to bring the levels of the whole track down, so it winds up being quieter when you're finished with it.

Luckily, there are some tricks you can use to get your tracks to sound louder. This is what we call dynamic range compression. A little bit is a good thing. Basically when you're mastering an audio track you make the peaks sounds a little bit quieter, and then you can bring the volume of the whole track up. This way, you can get your songs to sound a little bit louder, without worrying about clipping.

The problem is that some people get carried away. When you're a band with a song you want to promote, you want it to stand out in as many ways as possible. One of these ways is to make the song sound louder than other songs. It's kind of a no-brainer. It's also frustrating, speaking as somebody whose passion is working with recordings. If someone listens to two recordings of the same song, and one is louder than the other, he or she will probably tell you that the louder one 'sounds better', even if the only change you made was turning the volume knob.

Unfortunately, music is a business, so there's competition. If your music sounds better, more people will (theoretically) listen to it. Enter the downfall of recorded music as we know it. The average volume level of CDs has increased dramatically since their debut thirty years ago. Since CDs store sound digitally, audio engineers must use dynamic range compression to get the albums they make to sound louder. And since everyone wants their CDs to sound louder than the average, it means that CDs have been increasingly compressed as time has gone by. Just look. Here are two waveforms from two songs:

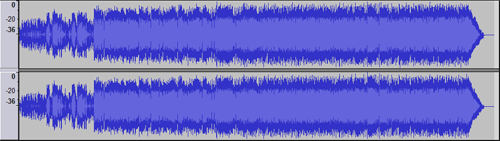

“Talkin' Bout a Revolution,” Tracy Chapman, 1988

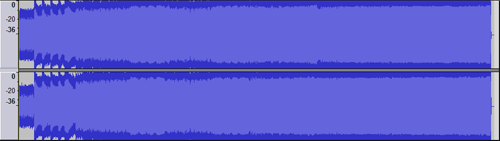

“The Day That Never Comes,” Metallica, 2008

The first song is “Talkin' Bout a Revolution” by Tracy Chapman, from her album Tracy Chapman, released in 1988. This is from the original CD release. What you're seeing is a visual representation of the sound. The taller the waveform is, the louder it sounds (in general). The second waveform looks a lot louder, and it is. It's from “The Day That Never Comes” by Metallica, from their 2008 album Death Magnetic. Twenty years later, and this album is so loud it's actually tiring to listen to. It's been compressed so much that the supposedly 'quiet' parts are louder than the loudest bit of Tracy Chapman's song.

And this is the problem. As someone who makes music, I have to compete, too. It's hard enough to get someone who's never heard of me to listen to my songs. If they happen to be so quiet that you have to turn your speakers up to hear them, they feel unprofessional and weak. So I also have to compress the dynamic range of my songs. This is unfortunate, because dynamic range lends a lot to a song's feeling or mood. When you squash a song so much that its waveform looks like the Metallica song above, you remove a lot of that mood. Instead of different sections of a song having different dynamics, you have one plodding mass of near-distortion. The sound pounds at your ears, until you can almost feel its relentless loudness, thumping out of the speakers at you like an army of jack-booted thugs. It sucks.

What I'm Doing

First, while I'm making my records louder, they're not nearly as loud as the prevailing sound of the times. I've got a radical idea for all the listeners out there: if you want a record you're playing to sound louder, you can turn up the volume. Radical idea, isn't it? I've decided that I'm going to keep my songs below an average level of around -12dB. This is a bit loud, but is still much quieter than the industry average. I'm also going to offer two versions of most tracks -- a compressed one, and a higher-quality track with much less dynamic range compression. The high-quality files will probably also be made available in FLAC or another lossless format, to improve fidelity even more. CDs will be the high-quality versions, with a computer data session containing MP3s of the loudened versions.

This is going to require a bit more work on my part, but I think it will be worth it in the end. I've been meaning to remaster my back catalog for a while now, and this will give me a chance to, and to do so without having to squash the holy hell out of my music.

What You Can Do

Unfortunately, most people don't care. They hear something louder and equate it with being better, despite how tiring it might be after prolonged (or even short-term) exposure. The choice to master the hell out of records is often out of the hands of the musicians themselves. Don't get angry with the audio engineers, either, because they're usually just following the orders of highers-up.

All you can do is let your favorite musicians know. Sometimes, they'll tell you to piss off (which is essentially what Metallica did.) But there are some other bands that probably feel the same way, and each e-mail or letter lets them know that more people care about this issue.

We're eventually going to get to a point where things can't get any louder without sounding terrible. If you ask me, Death Magnetic already fits that definition. What happens next depends on what we're willing to put up with. The music industry already prosecutes its fans, so I wouldn't put increasing the loudness wars to the point of absurdity past them.

More Information

- Wikipedia article: "Loudness war"

- The Loudness War Analyzed: lots of charts of the dynamic range of certain songs, some other charts, too. Plus Python source code!

- Turn Me Up has the right idea, but they're bogged down in creating a rigorous, repeatable approach to certifying that an album has more dynamic range than the norm.

- There's a good video on YouTube that probably does a better job explaining the Loudness War than I did.

Updates via

Updates via